A couple weeks ago, I posted about the prize that the Académie française awarded Louisiana writer Kirby Jambon for his book of poetry, Petites communions: Poèmes, chansons, et jonglements. I received my own copy of Mr. Jambon’s book almost the day after posting, and was instantly drawn into his style of writing. It’s easy to see why this work was recognized. The book is organized as a cohesive whole while also providing poems that feel fulfilling on their own. Form plays an important role in many pieces, sometimes with whole sections being written in particular styles, such as haikus about the weekend. Even the language itself feels fresh and modern, while still retaining its local identity, as it ranges from Louisiana Creole:

Mo gain pou couri

I have to go

To a sort of parodic literary Standard French:

Voici les paroles que le prophète Aïeux adressa à toute Descendance

Here are the words that the prophet Where addressed to all of Posterity

from Un passage du deuxième livre de l’Ancienne nouvelle

A passage from the second book of the Former news

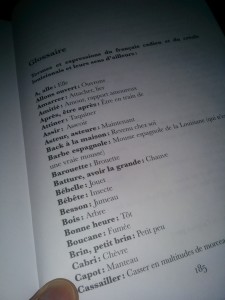

Something that immediately caught my eye, though, was the glossary I found in the back of the book. Definitions of lexical items and grammatical forms are listed that may not be familiar to French speakers from, say, Paris, and what was chosen to be included is interesting from a linguistic standpoint.

Grammatically, one finds the first person plural imperative form using allons instead of simply the first person plural present conjugations (i.e. allons danser vs dansons). This form isn’t unheard of outside of Louisiana, though perhaps the regularity of it here makes it somewhat of an indicator for this variety of French.

Morphologically, the infix -aill- is given to show a sort of negative, or more negative, sense to a word, as touched on by Thomas Klingler, professor of French at Tulane University (The Lexicon of Louisiana French 1997). For instance, casser (to break) is already inherently not a positive action–one would be hard pressed to think of instances where breaking something results in feeling happy–but cassailler suggests not only breaking something but breaking something valuable into a million pieces then stomping on it. Although I’m not certain how widely used this form is in other varieties of French, I have personally come across it in a popular video game (this is a topic that I intend to write about later on).

Of course, lexical differences themselves show up in the glossary as well, bois being one of them. This isn’t a completely unique word, rather it’s a word whose semantic extension goes beyond the normal usage, meaning forest or woods. In Louisiana, bois can refer to a single tree, particularly in Southeast Louisiana, where Mr. Jambon resides.

These three particular examples can add up to a phrase such as allons pas cassailler le bois, translated in the title of this post itself, which is an attempt to say something possibly unintelligible to many francophones while also taking poetic license to suggest that maybe we shouldn’t be so explicitly segregating Louisiana French from other varieties of the same language. Who is this glossary really for if not other francophones? Why is it necessary? Are we saying that our French is so incomprehensible to someone from Switzerland, for example, that we need to literally translate for them?

Personally, I feel like this is a rather unnatural way of creating (reinforcing?) mutual intelligibility. I remember at one time attempting to learn some Spanish by reading a collection of short stories entitled La increíble y triste historia de la Cándida Eréndira y de su abuela desalmada by Gabriel García Márquez and often coming across words and phrases that I could not make heads or tails of using translators and a Spanish textbook. To my surprise, my perfectly fluent Mexican friend who lent me the book also didn’t understand some of the words and phrases Márquez used read in isolation, yet a glossary was not provided. It must have been assumed that context alone would be enough to get Márquez’s ideas across to those unfamiliar with his dialect, which is exactly how this played out for my friend.

Of course, poetry is a different discussion. It is almost by its very nature vague, suggesting that we either need to have a deep understanding of each element being used to get the whole picture, or possibly that the whole picture requires that we don’t fully understand anyway. Perhaps this renders the issue moot from the get go in the case of Petites communions.

Recent Comments