While I’m on the topic of businesses that don’t seem to understand, why not touch on banks? I like banks. I’ve had bank accounts since I was legally able to open them and I find them useful. I don’t have a particular distrust of them or feel that they’re out to get me or anything like that. In fact, I currently have 3 banks accounts even though I don’t have nearly enough money to warrant that but I don’t see any harm in having them. So my criticism here, of TD Bank specifically, is not simply a matter of having an axe to grind against bankers or a tinfoil hat problem.

I opened an account with Commerce Bank back in the day, when they first opened in the northeast. They had long hours and no fees so it was great. Apparently, it wasn’t great for them as they eventually were bought out by TD Bank who decided to add fees back in. I’ve never had a problem with that. I had to keep $100 in the bank to avoid any fees, no biggie. I even accidentally went below that limit at some point over the years and called them to see if an exception could be made and it was. There was no arguing or anything so I was thrilled. Unfortunately, this wasn’t a case of understanding on the part of the CSR but simply a company policy that the first request of this sort that any customer makes can be granted but then never again.

Years later I no longer lived anywhere near a TD Bank location. I had really no reason to keep my account with them but the minimum fee was low enough that I didn’t care and I had a credit card with them so it made paying that directly from my checking account easier. Whenever I charged something, I’d transfer that amount into my checking account and pay off the balance from there immediately. One day I was doing this and, for some reason, entered $100 more as a payment to my credit card than I meant to. Instead of bringing my balance in my checking account down to $100 it brought it down to $0. An important note here is that, in reality, not a penny of the money I had with TD Bank changed, it was just located in a different place in their system. I realized my mistake and within minutes of making it transferred another $100 into my checking, hoping to avoid the maintenance fee. When my bill cycle came, I was charged the maintenance fee. I didn’t like paying it but it was clearly my mistake and I wasn’t interested in getting special favors to resolve something dumb that I did. And I figured that was it.

The next month came and I was charged another maintenance fee. I called this time because I had already paid this fee and made no more mistakes. The CSR this time was not nearly so pleasant. I spoke to more than one on my mission to find someone who was reasonable and eventually did come across a supervisor who recognized that I was only charged the successive fee because of the first fee brought my account under the minimum amount for a day. She refunded the fee but I e-mailed TD Bank to ensure that this wasn’t simply going to happen again the next month. These are the exchanges that followed (I apologize for their e-mail system managing chronology horribly):

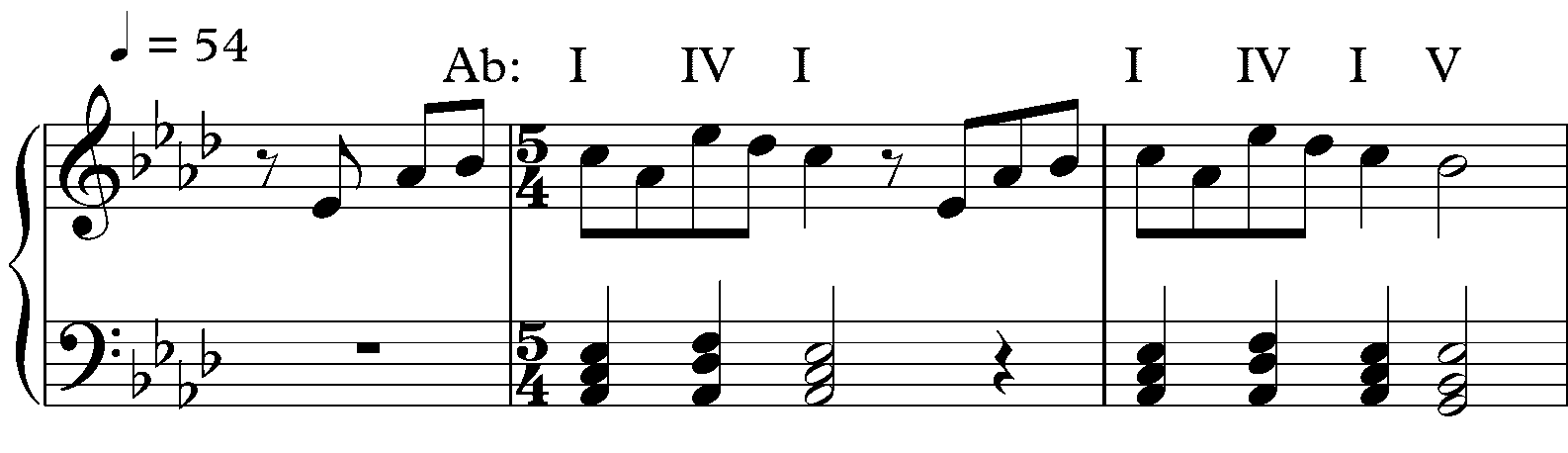

TD Bank Correspondence 1

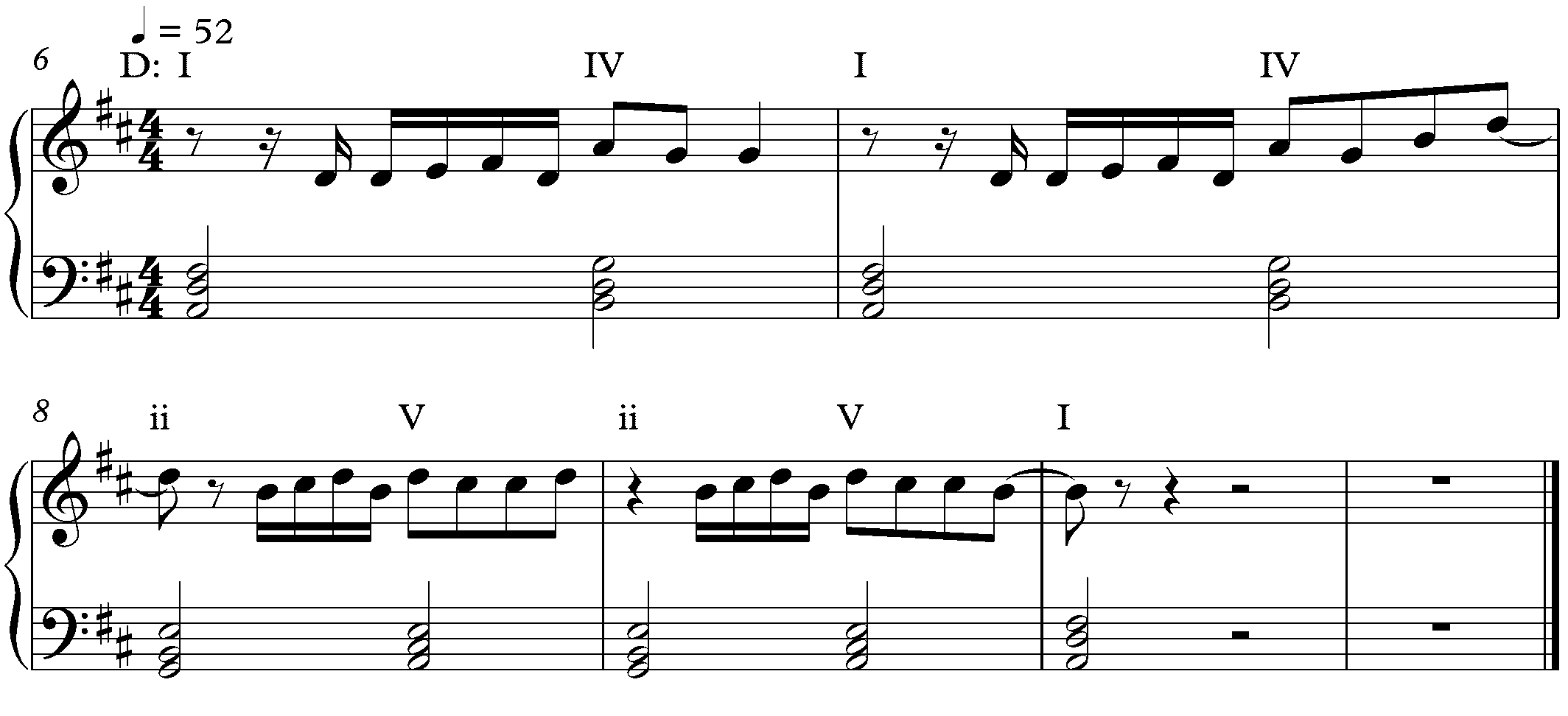

TD Bank Correspondence 2

I did, in fact, immediately withdraw my money and close my accounts to escape this fee loop.

I’ve wanted to send this correspondence to TD Bank directly at some point with a more verbose description of why I believe this to be ludicrous but, as always, the only e-mail address I can find for the company goes right to the same customer support people who I am criticizing. The wording is so strange. The claim that the bank understands my frustration while simultaneously not recognizing the absurdity of their behavior makes no sense at all to me. I understand that they can’t simply bypass fees for everyone in every instance, that they have to make the customer take responsibility at some point to maintain their capital, but this is exactly what I did. The failure was that they wanted me to perpetually take that responsibility or to deposit more capital for them to work with than the terms of my account required. It’s troubling that I couldn’t make them see how crazy this was and I think this is really why people hate banks. You’re often faced with people who are either not willing to or not able to look at their customers’ issues on a case by case basis. They respond with boiler plates and by quoting company policy instead of thinking critically about what your problem is and considering whether it’s you who needs to adjust or if their system needs to adjust to you. The latter possibility seems to never enter their minds.

I’m sure the result would have been different if I had hundreds of thousands of dollars in my account but why even attempt to run a bank that takes on small accounts if you see them as being more costly than valuable? They were probably glad to get rid of my account as the administration costs incurred through handling my calls and e-mails was probably greater than the $100 of capital I maintained with them for years. But why the charade in the first place? If you’re going to take on these customers, then take them on and treat them like real people. Any costs incurred on my account would have disappeared immediately if they had recognized my issue after the first communication and fixed it completely. That was literally the only call I had made to them in years. They most definitely profited from my small account even if they lose with other small accounts and yet they actively drove me away once I became even slightly an issue.

Banks still have a huge PR issue. People feel, rightly or wrongly, that they’ve run our economy into the ground then took all our tax money to give bonuses to their CEOs. Instances like mine go nowhere toward fixing that relationship. Like I said, I feel I’m a reasonable person when it comes to this topic and I have nothing against banks but an experience like this certainly moves me toward the “you are not my friend” frame of mind when I look at these institutions.

NOTE: I promise that my next post will not consist of more whining. For some reason it’s less time consuming to post this stuff than to compare Marilyn Mason to Cuban rhythms or to analyze the formants of vowels in comparison to tonal harmonic theory in music (these are both on the back-burner).

Recent Comments