I spoke about the way that one can create a false immersion environment using virtual worlds, but today I’d like to talk about the way one can make the most of the input that one receives in these worlds. That is to say, let’s talk about metalinguistic awareness.

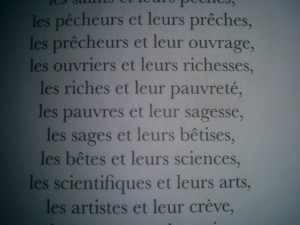

We can begin to understand this idea using an example from a poem by Kirby Jambom, who I already wrote about here and here. On the right, one can see a pattern: noun (plural) et leur(s) noun (singular/plural). The first noun is always plural while the second is either singular or plural. Since there are several people in each instance, one would expect that the second noun would be equal to the first, but that’s not the case. This is because of the difference between count nouns and mass nouns.

A count noun is a noun that one can modify with a number, like the word bêtise [joke] in this case. On can speak of several bêtises (i.e. deux bêtises, trois bêtises, etc.). On the contrary, one cannot speak of several pauvretés [poverties]. There’s only one, then no more, thankfully. For that reason, the word pauvreté is a mass noun.

Mr. Jambon’s text makes this difference clearly evident, but I’m pointing it out to demonstrate what “metalinguistic awareness” means. It means that one reads carefully. It means that one thinks about what one is reading then asks good questions. It’s as important to understand why one would say this or that as to understand what a phrase means. Always ask “why” when reading. Read carefully. It’s easier to learn a few rules than to memorize 3,000 phrases.

Recent Comments